Understanding Workaholism

Workaholism is valued in society due to cultural norms that equate long hours with dedication, the personal identity tied to professional success, organisational reinforcement of excessive work habits, and the illusion that constant busyness equates to productivity (Ulz, 2023)

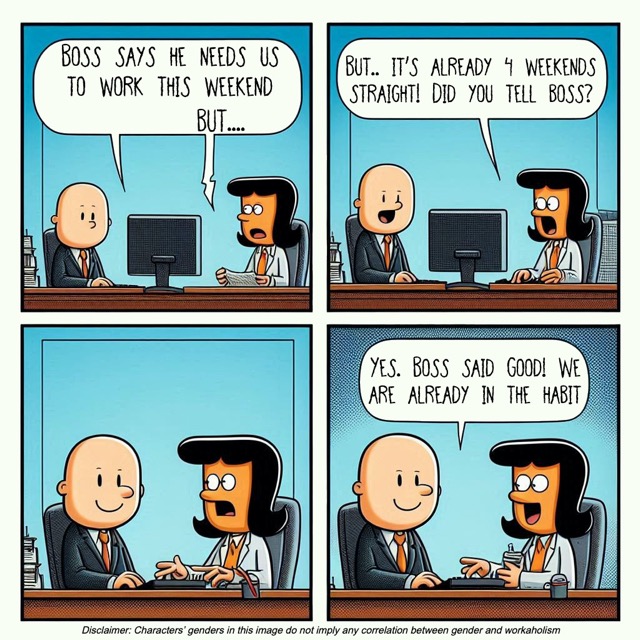

Workaholics often experience an initial boost in happiness from their accomplishments, but this feeling is transient, leading them to seek further achievements to regain that satisfaction (Malinowska & Tokarz, 2014). As a result, workaholics may feel compelled to pursue even greater achievements to regain that fleeting sense of satisfaction, leading to a continuous cycle of striving and disappointment.

Furthermore, modern consumer culture promotes the idea that acquiring more—whether it be material possessions or professional accolades—will lead to greater happiness. Workaholics may find themselves caught in this mindset whether it be material possessions or professional accolades—believing that their worth is tied to their productivity and achievements. However, these materialistic pursuits often yield only temporary satisfaction, leading to a continuous cycle of seeking the next accomplishment or possession.

Moreover,

After the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, academic staff at Menoufia University found that the frequency of workaholism rose from 33% to 46.4%. This increase is attributed to the shift to remote work and the blurring of boundaries between personal and professional life, leading many individuals to work longer hours without clear separation from their home life (Allam et al., 2021)

And,

Authoritarian leadership styles exacerbated the relationship between workaholism and technostress, indicating that poor leadership can intensify the negative effects of workaholic tendencies. Employees under authoritarian leaders faced increased pressure to remain constantly available, further blurring the lines between work and personal time (Spagnoli et al., 2020)

Smartphones, ubiquitous internet connectivity, and productivity apps has blurred the lines between work and personal life, creating an environment ripe for workaholic tendencies. This technological landscape enables constant connectivity to our professional responsibilities, making it increasingly challenging to "log off" from work.

Additionally, workaholics may evaluate their happiness based on how they measure up to others in their professional environment. This social comparison can create pressure to work harder and achieve more, further entrenching the cycle of workaholism. The constant need to keep up with or surpass others’ achievements can lead to increased stress and dissatisfaction.

Evolution of Perspectives on Workaholism

However, the perspectives of workaholism have expanded from a narrow, purely negative view to a more complex, multidimensional understanding that recognises both potential positive and negative aspects of workaholism. There is now greater emphasis on identifying different types and considering various factors that influence whether workaholism is functional or dysfunctional.

| Era |

Perspective |

Key Features |

Relevant Research & Context |

| 1. Early Definitions (1970s-1980s) |

Single-dimensional |

- Defined as "addiction to work"

- Based on number of hours worked

- Purely negative view

|

- Oates (1971): "addiction to work, the compulsive and uncontrollable need to work incessantly"

- Mosier (1983): Classified workers as workaholics if they worked over 50 hours/week

|

| 2. Positive Perspective (Late 1970s-1980s) |

Positive view |

- Viewed as devotion to work

- Emphasized deriving pleasure from hard work

|

- Cantarow (1979): Described workaholism as "devotion to work"

- Machlowitz (1980): Saw workaholism as manifestation of inner need to work hard and derive pleasure

|

| 3. Multidimensional Approach (1990s) |

Three-dimensional |

- Work involvement

- Drive to work

- Work enjoyment

- Recognized both positive and negative types

|

- Spence and Robbins (1992): Proposed three-dimensional model

- Introduced "enthusiastic work addicts" and "non-enthusiastic work addicts"

|

| 4. Refinement of Concepts (2000s) |

Narrowing focus |

- Work enjoyment dimension questioned

- Work involvement subscale found invalid

- Focus on compulsion and drive

|

- Mudrack (2006): Questioned relevance of work enjoyment

- Andreassen et al. (2013b): Found work involvement subscale invalid

- Schaufeli et al. (2008): Emphasized working compulsively and excessively

|

| 5. Shift Towards Addiction Model (2010s) |

Addiction-based |

- Viewed as behavioral addiction

- Incorporated addiction components

|

- Andreassen et al. (2012): Developed Bergen Work Addiction Scale based on addiction components

- Griffiths (2005, 2011): Applied components model of addiction to workaholism

|

| 6. Differentiation from Work Engagement (2010s-present) |

Separating constructs |

- "Enthusiastic work addiction" replaced by "work engagement"

- "Workaholism" reserved for negative aspects

|

- Taris et al. (2020): Discussed the distinction between workaholism and work engagement

- Andreassen (2013): Noted the shift in terminology

|

| 7. Debate on Terminology (2010s-present) |

Semantic discussions |

- Debate on differentiating "workaholism" from "work addiction"

|

- Griffiths et al. (2018): Argued for distinction between terms

- Andreassen et al. (2018b): Maintained they refer to the same construct

|

| 8. Current State (Present) |

Fragmented but integrative |

- Lack of common ground among experts

- Various measurement tools

- Attempts to integrate different viewpoints

- Recognition of complexity and various manifestations

|

- Andreassen (2013): Reviewed different conceptualizations and measurements

- Molino et al. (2022): Found inconsistent correlations between different operationalizations of workaholism

- Current research: Considers both potential positive and negative aspects

|

This table highlights the initial purely negative view, the subsequent recognition of potential positive aspects, the development of multidimensional models, the shift towards an addiction-based perspective, and the current state of ongoing debates and attempts at integration . The field continues to grapple with defining, operationalising, and measuring workaholism, reflecting the complexity of work-related behaviours in modern society.

Understanding this scholarly evolution provides a crucial context for our subsequent Buddhist analysis. Workaholism is a complex phenomenon that defies simple categorisation, much like the Buddhist understanding of human behaviour and motivation. The latest research underscores the need for a holistic approach to understanding and addressing workaholism, which aligns well with Buddhist principles of interdependence and contextual awareness.

A Buddhist Perspective on Work Addiction

From a Buddhist viewpoint, constant engagement with work-related stimuli can be understood through several key concepts:

1. Manasikāra (Attention) and Vitakka (Initial Application of Mind)

The ease with which we can direct our attention (manasikāra) to work-related tasks through our devices, coupled with the habitual thought patterns (vitakka) surrounding productivity and success, creates a potent combination that can lead to work addiction.

To illustrate this concept, consider the common scenario of checking work emails late at night. The notification sound triggers our attention (manasikāra), and our mind immediately applies itself to work-related thoughts (vitakka). This seemingly small action can set off a chain of work-related activities, pulling us back into professional mode when we should be resting or engaging in personal activities.

2. Vedanā (Feeling Tone) and Taṇhā (Craving)

The cycle of workaholism mirrors the Buddhist understanding of how craving leads to suffering:

-

Craving or attachment is seen as the root of suffering. For the workaholic, this might manifest as an insatiable desire for professional success or recognition, or simply one cannot stay still.

-

All phenomena are transient as is the joy of achievements. It is often short-lived.

-

Continual pursuit of external rewards does not and can not lead to lasting happiness.Specifically, this cycle can be understood through the concept of "vedanā" (feeling tone) and its relationship to "taṇhā" (craving). The pleasant vedanā associated with work accomplishments gives rise to craving for more such experiences, perpetuating the cycle of dissatisfaction and striving.:

To illustrate this connection:

When a worker receives a promotion, they initially experience joy and satisfaction (sukha vedanā). However, this positive feeling soon fades (demonstrating anicca or impermanence). The worker then constantly continues to work at “full force”, initially driven by the motivation of the promotion, and subsequently the desire to “live up” to expectations after the promotion. The expectations to perform or achieve the next milestone (taṇhā) set in motion the cycle of dissatisfaction (dukkha).

This cycle can be further understood through the relationship between feeling (vedanā) and craving (taṇhā). The pleasant feeling (vedanā) associated with work accomplishments gives rise to craving (taṇhā) for more such experiences. This craving perpetuates the cycle of dissatisfaction and striving, as the worker is unable to be fully satisfied with their current state and constantly seeks the next achievement or promotion to maintain the positive feeling or is pressured to not disappoint and meet expectations to preserve the self-esteem or identity and to remain dedicated.

To break free from this cycle, we must first recognise its operation in our lives. Take a moment to reflect on your work habits. Do you feel a brief sense of satisfaction after completing a task, only to immediately seek out the next challenge? Do you find yourself constantly refreshing your email or checking your phone for work-related updates, even during personal time?

The Buddhist teachings emphasise that this cycle is rooted in the fundamental human tendency to crave and grasp at pleasant experiences while avoiding unpleasant ones. In the case of workaholism, the worker becomes attached to the positive feelings associated with professional success and recognition. However, as these feelings are impermanent, the worker is caught in a perpetual cycle of seeking and grasping, leading to increased stress, burnout, and a lack of work-life balance.

To break free from this cycle, the Buddhist path suggests cultivating mindfulness and insight into the nature of vedanā, taṇhā, and dukkha. By recognizing the impermanent and unsatisfactory nature of all conditioned phenomena, including professional achievements, the worker can develop a more balanced perspective and let go of the attachment to constant striving and success. This allows for the cultivation of a more sustainable and fulfilling approach to work and life.

3. Sankhāra (Mental Formations) in Work Habits

Recognising the conditioned nature of our work-related thoughts and behaviours allows us to see them as impermanent and subject to change. This understanding can help loosen the grip of workaholic tendencies. Here's how to apply this concept:

-

Keep a "work habits" journal for a week. Note down your automatic responses to work situations, such as immediately checking emails when you wake up or working through lunch breaks.

-

For each habit you’ve identified, reflect on its origins. When did you develop this habit? What beliefs or fears might be driving it?

-

Choose one habit to modify. Remind yourself daily that this habit is a conditioned response, not an inherent part of who you are. Experiment with different responses and observe how this changes your experience of work.

By engaging in this practice, you’ll start to see your work habits as flexible and changeable, rather than fixed aspects of your personality or professional life.

Breaking the Cycle: Buddhist-Inspired Approaches

1. Developing Upekkhā (Equanimity) Towards Professional Outcomes

Cultivating equanimity towards both success and failure in our work life can help us step off the hedonic treadmill. This doesn’t mean becoming indifferent, but rather maintaining a balanced perspective on our professional journey. Here's how to develop this quality:

-

At the end of each workday, take a few minutes to reflect on your accomplishments and setbacks. Acknowledge them without judgment, recognising that both are natural parts of any professional journey.

-

Practice a brief loving-kindness (mettā) meditation focused on yourself as a professional. Offer wishes for your own well-being and success, but also for your ability to handle challenges and disappointments with grace.

-

When faced with a significant work outcome (positive or negative), pause to observe your emotional reaction. Remind yourself that this, too, is impermanent and does not define your worth or your entire professional journey.

By consistently practicing these exercises, you'll develop a more balanced emotional approach to your work life, reducing the extreme highs and lows that can fuel workaholic tendencies.

2. Wise Attention and Wise Engagement

“Wise attention” or “appropriate attention”, is a fundamental concept in Buddhist practice that can be powerfully applied to our relationship with work and technology use. Wise Attention involves directing our attention in a way that is conducive to understanding reality as it is, free from delusion and attachment. In the context of work and technology, it means critically examining our habits, motivations, and the true value of our activities. Wise engagement, building upon this foundation, refers to interacting with our professional lives and digital tools in a manner that aligns with our deeper values and contributes to genuine well-being.

These concepts are particularly relevant in our modern work environment, where constant connectivity and the pressure to be productive can lead us astray from what truly matters. By cultivating wise attention, we can see through the illusions of urgent but unimportant tasks, the false promises of multitasking, and the allure of constant digital engagement. This clarity then allows us to engage wisely with our work and technology, making conscious choices that support our well-being and effectiveness.

To develop wise attention in relation to work and technology, consider the following practices:

- Intentional Pauses: Before engaging with any work task or digital tool, take a brief moment to ask yourself:

- What is my intention in doing this?

- Is this action truly necessary and beneficial?

- How does this align with my values and goals?

- Mindful Task Selection: When faced with multiple tasks or notifications, practice discernment:

- Which of these tasks will have the most meaningful impact?

- Am I choosing this task out of genuine necessity, or out of habit or avoidance?

- How does this task contribute to my long-term objectives?

- Technology Awareness: Pay close attention to your use of digital tools:

- Notice the impulse to check devices or refresh feeds. What triggers this impulse?

- Observe how different digital interactions affect your mental state and energy levels.

- Regularly assess whether your use of technology is supporting or hindering your work and well-being.

- Value-Aligned Action: Regularly reflect on how your work aligns with your core values:

- Are your daily activities contributing to what you consider truly important?

- How can you adjust your work to better reflect your values?

- What aspects of your work bring a sense of meaning and fulfilment?

To cultivate wise engagement based on this foundation of wise attention:

- Structured Digital Engagement: Create clear boundaries for technology use:

- Designate specific times for checking emails and messages, rather than responding to every notification.

- Use tools like website blockers or app timers to limit access to distracting sites during focused work periods.

- Mindful Communication: Bring attention to your digital communications:

- Before sending an email or message, pause to consider its necessity and potential impact.

- Practice empathy in digital communications, considering the recipient's perspective and needs.

- Purposeful Productivity: Approach your work with clear intention:

- Start each day or work session by setting clear, meaningful objectives.

- Regularly step back to ensure your actions are aligned with these objectives.

- Celebrate progress and completion of tasks, acknowledging the value of your work.

- Holistic Self-Care: Recognize that wise engagement extends beyond work tasks:

- Schedule regular breaks and time for physical movement.

- Prioritise activities that nourish your mind and body, seeing them as essential to your overall productivity and well-being.

- Practice transitioning mindfully between work and personal time, creating clear delineations in your day.

- By consistently applying wise attention to your work life, you'll naturally prioritise activities that are truly meaningful and impactful, rather than getting caught up in busy work or unnecessary stress.

From Workaholism to Mindful Productivity

The path from digital-age workaholism to mindful productivity is not about rejecting technology or ambition, but about cultivating a wiser, more balanced engagement with our professional lives. This approach allows us to contribute meaningfully in our professional lives while maintaining balance, mindfulness, and alignment with our deepest values. It’s a path that leads not just to productivity, but to genuine fulfilment and well-being in our interconnected, digital world. As you implement these practices, be patient with yourself and celebrate small changes.