In the digital age, the world has become more connected than ever before. Social media platforms have become an important part of our daily lives, providing a virtual landscape for communication, networking, and self-expression. Yet, as we revel in the interconnectedness these platforms offer, there is a side that thrives on deception, manipulation, and exploitation.

Social engineering, is a craft. A clever blend of psychology and deception that preys upon human trust and behavior, tricking individuals into revealing sensitive information, clicking malicious links, or taking actions that compromise their security working against their own welfare. In an environment where connections and trust are cultivated, social media is undoubtedly the perfect breeding ground.

This article discusses the unsettling reality of how enhanced interconnectivity has become a powerful catalyst for the rise of social engineering attacks.Welcome to the dark side of of connectivity in the 21st century.

| As we revel in the interconnectedness of online networks, a shadowy side persists |

|---|

|

What is Social Engineering?

Social Engineering is an art.

It is the digital magician's art, that manipulates human psychology rather than pulling rabbits out of hats. It is about exploiting trust, curiosity, and the willingness to help that resides within each of us.

It leverages our natural tendency to trust others, especially when they appear friendly, authoritative, or familiar. By impersonating trusted sources or manipulating emotions like fear or urgency, the social engineers create the perfect conditions for their illusions.

How do they do that?

They study their targets, collecting information from social media profiles, forums, or company websites. They then craft tailored attacks that resonate with their victims' interests, concerns, or roles. This personalization makes the deceit more convincing.

In Summary:

Social engineering is an attack vector that relies heavily on human interaction and often involves manipulating people into breaking normal security procedures and best practices to gain unauthorized access to systems, networks, or physical locations or for financial gain.

Social engineering attacks can be used to steal employees' confidential information, spread malware, or gain access to sensitive data or systems.

Social engineers use a variety of tactics to perform attacks, including phishing, spear phishing, CEO fraud, and pig butchering scams.

Perspectives of Social Engineering Attacks

All social engineering techniques are based on specific attributes of human decision-making known as cognitive biases, which are exploited in various combinations to create attack techniques.

| Key Perspectives of Social Engineering |

|---|

|

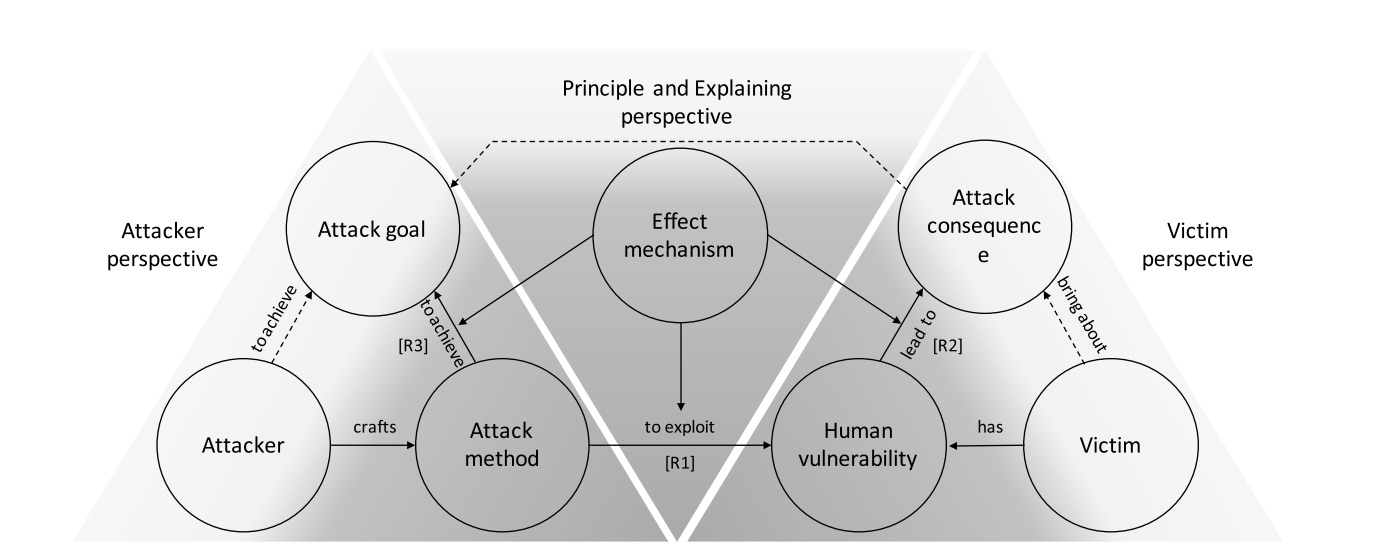

There are three main views to understand how social engineering attacks work, as shown in Figure above by [1].

-

The Attacker's Angle: Attackers plan their attacks by choosing how to do them. Think of it as their strategy. More advanced and clever strategies are more likely to succeed.

-

The Victim's View: These attacks work because people have weaknesses or vulnerabilities. Attackers take advantage of these weaknesses, and victims try to get rid of or lessen them. Sometimes, attackers also use other weaknesses, like flaws in computer programs, in addition to human vulnerabilities, but they don't always need to.

-

Principle and Explaining Perspective: We can understand how attack methods use these human vulnerabilities to make the attack successful by looking at "effect mechanisms." These mechanisms explain why these weaknesses lead to the results of the attack and how the attack methods achieve their goals. Effect mechanisms show the link between what happens during an attack and the vulnerabilities in people, in specific attack situations.

Principles Behind Social Engineering

From a psychological perspective, social engineering is intricately related to the process of decision-making. This is because, due to the limitations of cognitive capacity, individuals often rely on heuristics when making choices. These heuristics, are shaped by both experience and genetics, and are generally effective in guiding decisions in typical situations. However, when these heuristics fail to provide accurate guidance, cognitive biases can emerge.

Social engineers, essentially the perpetrators of such deceptive actions, possess a keen understanding of the vulnerabilities within human reasoning. They strategically manipulate the heuristics of their targets, pushing them toward systematic errors, which are known as cognitive biases. This manipulation ultimately coerces their targets into compliance.

They craft scenarios that trigger emotional responses and create situations that prompt cognitive dissonance, ultimately leading individuals down a path of deception and compromise.

The list below is non-exhaustive but are some of the more common ones.

Social Proof

Robert Cialdini, in Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion [2], describes that individuals tend to follow the actions of others, assuming that if many people are doing something, it must be right.Social engineers exploit this by creating the illusion of consensus, making targets more likely to comply with deceptive requests.

The book outlined 6 universal principles of influence and show us how we can become skilled persuader, and how to defend ourselves against dishonest attempts:

- Reciprocation: The internal pull to repay what another person has provided us.

- Commitment and Consistency: Once we make a choice or take a stand, we work to behave consistently with that commitment in order to justify our decisions.

- Social Proof: When we are unsure, we look to similar others to provide us with the correct actions to take. And the more, people undertaking that action, the more we consider that action correct.

- Liking: The propensity to agree with people we like and, just as important, the propensity for others to agree with us, if we like them.

- Authority: We are more likely to say “yes” to others who are authorities, who carry greater knowledge, experience or expertise.

- Scarcity: We want more of what is less available or dwindling in availability.

The Case:

In 2018, a group of scammers used social media to trick people into investing in a fake cryptocurrency called Giza. The scammers created fake social media profiles and used them to post positive comments about Giza, making it seem like the cryptocurrency was gaining popularity. They also created a fake Telegram group and used bots to make it seem like there were many people discussing Giza. As a result, many people invested in Giza, believing that it was a legitimate investment opportunity.

Authority

The Milgram Experiment by Stanley Milgram revealed how people tend to obey authority figures, even when instructed to perform actions that go against their moral beliefs [3]. It was one of the most criticised obedience experiment.

Sixty-six percent of the participants exhibited no hesitation in administering a lethal dose of 450 V to a human subject, as explicitly instructed by an individual they believed possessed genuine authority. Milgram developed the Agency Theory in response to his study. This theory states that humans in an autonomous state act according to their own will, but humans in an agentic state choose to act according to the will of a person in authority.

An analysis of 23 replication studies, spanning a period of 35 years, delved into the obedience to authority paradigm. Among these studies, 11 studies, reported a reduced level of compliance compared to the original Milgram study, with rates ranging from 28% to 65%. Conversely, the remaining 12 studies documented either equal or elevated levels of compliance, with rates spanning from 66% to 91%. Despite variations in observed rates of obedience, it can be reasonably concluded that the concept of authority significantly influences human behavior [4].

Social engineers often impersonate authority figures or exploit perceived authority within organizational hierarchies to manipulate victims into compliance.

The Case

In 2019, a group of scammers used Twitter to impersonate the support team of a major cryptocurrency exchange, BitMEX. The scammers created a fake Twitter account that looked like the real BitMEX support account and then replied to tweets from users who were having issues with their accounts. The scammers would then ask the users to provide their account information, such as their login credentials or two-factor authentication codes, under the guise of helping them resolve their issues. By posing as legitimate customer support representatives, the scammers were able to establish authority and gain the trust of the users, making it more likely that the users would comply with their requests.

Reciprocity

Robert Cialdini's work also introduced the principle of reciprocity, where individuals feel obliged to return favors or gestures of kindness. For example, in the concept of reciprocal concessions, commonly referred to as the "door-in-the-face" technique (abbreviated as DitF), achieving compliance involves an initial rejection of an extreme request, followed by the presentation of a more moderate alternative. It's a strategic move where the requester modifies the initial proposal, prompting a corresponding adjustment in the recipient's response, ultimately transitioning from a "no" to a "yes". Social engineers may initiate interactions by offering seemingly benign favors or assistance, creating a sense of indebtedness in their targets, which can be exploited later.

The Case:

In 2017, a group of scammers used LinkedIn to target employees of a major US defense contractor. The scammers created fake LinkedIn profiles and sent connection requests to the employees, posing as recruiters or other professionals in the defense industry. Once the employees accepted the connection requests, the scammers would send them a message thanking them for connecting and offering to share job opportunities or other information. In some cases, the scammers would even send the employees a gift, such as a USB drive or a Starbucks gift card, as a way of establishing reciprocity. Once the employees had been "primed" with these small favors, the scammers would then ask them to download a malicious file or click on a phishing link

Note: The “foot-in-the-door” (FitD) technique also known as commitment Once a person has been induced to comply with a small request, he or she is more likely to comply with a larger demand.

Trust and Familiarity

The Mere Exposure Effect, studied by Robert Zajonc, suggests that people tend to develop a preference for things or individuals they are exposed to repeatedly.

In a study (Study 1) on ethical preference [5] reported substantial contrast in ethical tolerance across 12 out of 16 scenarios between individuals who have encountered such situations and those who haven't (Mere Exposure). Those with prior exposure tend to be more lenient towards ethically questionable actions.

Likewise, the outcomes from Study 2 reported significant divergence in ethical assessment across 9 out of 16 scenarios between those who have prior exposure and those who haven't. Once again, individuals previously exposed to these situations tend to adopt a more accommodating attitude towards ethically ambiguous behavior.

This findings suggests supports the Mere Exposure Effect within the context of social engineering persuasion. In social engineering, attackers create a sense of familiarity, often through well-crafted impersonations or profiles, making victims more likely to trust them.

Emotional Manipulation

Fear and urgency, often employed by social engineers, trigger emotional responses that cloud judgment and lead individuals to act hastily. This aligns with the emotional theories of psychologists like Paul Ekman, who explored universal human emotions.

Some of these have earlier been discussed in task scams, and in this pig butchering article, on how psychology is a technology for persuasion and then how one can develop security awareness and habituation based on the principle of mindfulness.

Cognitive Dissonance

Leon Festinger, suggests that individuals strive for internal consistency in their beliefs and actions. Cognitive dissonance theory, states that one experiences a sense of discomfort or disharmony (referred to as dissonance) when simultaneously holding two psychologically incompatible cognitions, such as thoughts or beliefs. In response to this discomfort, one often engages in cognitive adjustments, particularly when external influences alone cannot sufficiently justify one's actions. Cognitive dissonance can occur, for instance, in situations where one faces a crucial decision between two equally appealing alternatives. In such cases, one might subjectively choose one option even when rational reasons support the other, or one might recall the merits of the option rejected alongside the drawbacks of the one chosen. To alleviate this cognitive dissonance, one may justify the choice by adapting thoughts and even altering recollections, or one may modify behavior to align with the decision.

Social engineers exploit this by creating situations where victims experience discomfort due to conflicting information, pushing them to resolve the dissonance through actions that benefit the attacker (see nft scams).

References

[1] Wang, Z., Zhu, H. and Sun, L., 2021. Social engineering in cybersecurity: Effect mechanisms, human vulnerabilities and attack methods. IEEE Access, 9, pp.11895-11910.

[2] Cialdini, R.B., 2006. Influence: The psychology of persuasion, revised edition of Harper Business. ISBN-13, pp.978-0061241895.

[3] Tarnow, E., 2005. The Social Engineering Solution to the Murder in the Milgram Experiment. Social Psychology, 6(2), pp.1-8.

[4] Bullée, J.W.H., Montoya, L., Pieters, W., Junger, M. and Hartel, P., 2018. On the anatomy of social engineering attacks—A literature‐based dissection of successful attacks. Journal of investigative psychology and offender profiling, 15(1), pp.20-45.

[5] Weeks, W.A., Longenecker, J.G., McKinney, J.A. and Moore, C.W., 2005. The role of mere exposure effect on ethical tolerance: A two-study approach. Journal of Business Ethics, 58, pp.281-294.